Executable and Linkable Format (ELF)

Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) is the default binary format on Linux-based systems. It is used for executable files, object files, shared libraries, and core dumps.

Executable header

Every ELF file starts with an executable header, which is just a structured series of bytes telling you that it’s an ELF file, what kind of ELF file it is, and where in the file to find all the other contents. The executable header is represented in /usr/include/elf.h as a C struct called Elf64_Ehdr:

#define EI_NIDENT (16)

typedef struct

{

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT]; /* Magic number and other info */

Elf32_Half e_type; /* Object file type */

Elf32_Half e_machine; /* Architecture */

Elf32_Word e_version; /* Object file version */

Elf32_Addr e_entry; /* Entry point virtual address */

Elf32_Off e_phoff; /* Program header table file offset */

Elf32_Off e_shoff; /* Section header table file offset */

Elf32_Word e_flags; /* Processor-specific flags */

Elf32_Half e_ehsize; /* ELF header size in bytes */

Elf32_Half e_phentsize; /* Program header table entry size */

Elf32_Half e_phnum; /* Program header table entry count */

Elf32_Half e_shentsize; /* Section header table entry size */

Elf32_Half e_shnum; /* Section header table entry count */

Elf32_Half e_shstrndx; /* Section header string table index */

} Elf32_Ehdr;

e_ident

The executable header (and the ELF file) starts with a 16-byte array called e_ident. The e_ident array always starts with a 4-byte “magic value” identifying the file as an ELF binary. The magic value consists of the hexadecimal number 0x7f, followed by the ASCII character codes for the letters E, L, and F. Having these bytes right at the start is convenient because it allows tools such as file, as well as specialized tools such as the binary loader, to quickly discover that they’re dealing with an ELF file.

/* Fields in the e_ident array. The EI_* macros are indices into the

array. The macros under each EI_* macro are the values the byte

may have. */

#define EI_MAG0 0 /* File identification byte 0 index */

#define ELFMAG0 0x7f /* Magic number byte 0 */

#define EI_MAG1 1 /* File identification byte 1 index */

#define ELFMAG1 'E' /* Magic number byte 1 */

#define EI_MAG2 2 /* File identification byte 2 index */

#define ELFMAG2 'L' /* Magic number byte 2 */

#define EI_MAG3 3 /* File identification byte 3 index */

#define ELFMAG3 'F' /* Magic number byte 3 */

/* Conglomeration of the identification bytes, for easy testing as a word. */

#define ELFMAG "\177ELF"

#define SELFMAG 4

Following the magic value, there are a number of bytes that give more detailed information about the specifics of the type of ELF file. In elf.h, the indexes for these bytes (indexes 4 through 15 in the e_ident array) are symbolically referred to as EI_CLASS, EI_DATA, EI_VERSION, EI_OSABI, EI_ABIVERSION, and EI_PAD, respectively.

#define EI_CLASS 4 /* File class byte index */

#define ELFCLASSNONE 0 /* Invalid class */

#define ELFCLASS32 1 /* 32-bit objects */

#define ELFCLASS64 2 /* 64-bit objects */

#define ELFCLASSNUM 3

The EI_CLASS byte denotes whether the binary is for a 32-bit or 64-bit architecture. In the former case, the EI_CLASS byte is set to the constant ELFCLASS32 (which is equal to 1), while in the latter case, it’s set to ELFCLASS64 (equal to 2).

#define EI_DATA 5 /* Data encoding byte index */

#define ELFDATANONE 0 /* Invalid data encoding */

#define ELFDATA2LSB 1 /* 2's complement, little endian */

#define ELFDATA2MSB 2 /* 2's complement, big endian */

#define ELFDATANUM 3

The EI_DATA byte indicates the endianness of the binary. A value of ELFDATA2LSB (equal to 1) indicates little-endian, while ELFDATA2MSB (equal to 2) means big-endian.

#define EI_VERSION 6 /* File version byte index */

/* Value must be EV_CURRENT */

The next byte, called EI_VERSION, indicates the version of the ELF specification used when creating the binary. Currently, the only valid value is EV_CURRENT, which is defined to be equal to 1.

#define EI_OSABI 7 /* OS ABI identification */

#define ELFOSABI_NONE 0 /* UNIX System V ABI */

#define ELFOSABI_SYSV 0 /* Alias. */

#define ELFOSABI_HPUX 1 /* HP-UX */

#define ELFOSABI_NETBSD 2 /* NetBSD. */

#define ELFOSABI_GNU 3 /* Object uses GNU ELF extensions. */

#define ELFOSABI_LINUX ELFOSABI_GNU /* Compatibility alias. */

#define ELFOSABI_SOLARIS 6 /* Sun Solaris. */

#define ELFOSABI_AIX 7 /* IBM AIX. */

#define ELFOSABI_IRIX 8 /* SGI Irix. */

#define ELFOSABI_FREEBSD 9 /* FreeBSD. */

#define ELFOSABI_TRU64 10 /* Compaq TRU64 UNIX. */

#define ELFOSABI_MODESTO 11 /* Novell Modesto. */

#define ELFOSABI_OPENBSD 12 /* OpenBSD. */

#define ELFOSABI_ARM_AEABI 64 /* ARM EABI */

#define ELFOSABI_ARM 97 /* ARM */

#define ELFOSABI_STANDALONE 255 /* Standalone (embedded) application */

If the EI_OSABI byte is set to nonzero, it means that some ABI- or OS-specific extensions are used in the ELF file; this can change the meaning of some other fields in the binary or can signal the presence of nonstandard sections. The default value of zero indicates that the binary targets the UNIX System V ABI.

#define EI_ABIVERSION 8 /* ABI version */

The EI_ABIVERSION byte denotes the specific version of the ABI indicated in the EI_OSABI byte that the binary targets. You’ll usually see this set to zero because it’s not necessary to specify any version information when the default EI_OSABI is used.

#define EI_PAD 9 /* Byte index of padding bytes */

The EI_PAD field actually contains multiple bytes, namely, indexes 9 through 15 in e_ident. All of these bytes are currently designated as padding; they are reserved for possible future use but currently set to zero.

To inspect the e_ident array of an ELF binary (in this case the a.out from hello.c):

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ readelf -h a.out

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: DYN (Position-Independent Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x1060

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 13976 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 13

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 31

Section header string table index: 30

e_type, e_machine, and e_version

After the e_ident array comes a series of multibyte integer fields.

e_type specifies the type of the binary, with values ET_REL (relocatable object file), ET_EXEC (executable binary), and ET_DYN (a dynamic library).

/* Legal values for e_type (object file type). */

#define ET_NONE 0 /* No file type */

#define ET_REL 1 /* Relocatable file */

#define ET_EXEC 2 /* Executable file */

#define ET_DYN 3 /* Shared object file */

#define ET_CORE 4 /* Core file */

#define ET_NUM 5 /* Number of defined types */

#define ET_LOOS 0xfe00 /* OS-specific range start */

#define ET_HIOS 0xfeff /* OS-specific range end */

#define ET_LOPROC 0xff00 /* Processor-specific range start */

#define ET_HIPROC 0xffff /* Processor-specific range end */

e_machine denotes the architecture that the binary is intended to run on:

/* Legal values for e_machine (architecture). */

#define EM_NONE 0 /* No machine */

#define EM_M32 1 /* AT&T WE 32100 */

#define EM_SPARC 2 /* SUN SPARC */

#define EM_386 3 /* Intel 80386 */

#define EM_68K 4 /* Motorola m68k family */

#define EM_88K 5 /* Motorola m88k family */

#define EM_IAMCU 6 /* Intel MCU */

#define EM_860 7 /* Intel 80860 */

#define EM_MIPS 8 /* MIPS R3000 big-endian */

#define EM_S370 9 /* IBM System/370 */

#define EM_MIPS_RS3_LE 10 /* MIPS R3000 little-endian */

/* reserved 11-14 */

#define EM_PARISC 15 /* HPPA */

/* reserved 16 */

#define EM_VPP500 17 /* Fujitsu VPP500 */

#define EM_SPARC32PLUS 18 /* Sun's "v8plus" */

#define EM_960 19 /* Intel 80960 */

#define EM_PPC 20 /* PowerPC */

#define EM_PPC64 21 /* PowerPC 64-bit */

#define EM_S390 22 /* IBM S390 */

#define EM_SPU 23 /* IBM SPU/SPC */

/* reserved 24-35 */

#define EM_V800 36 /* NEC V800 series */

#define EM_FR20 37 /* Fujitsu FR20 */

#define EM_RH32 38 /* TRW RH-32 */

#define EM_RCE 39 /* Motorola RCE */

#define EM_ARM 40 /* ARM */

#define EM_FAKE_ALPHA 41 /* Digital Alpha */

#define EM_SH 42 /* Hitachi SH */

#define EM_SPARCV9 43 /* SPARC v9 64-bit */

#define EM_TRICORE 44 /* Siemens Tricore */

#define EM_ARC 45 /* Argonaut RISC Core */

#define EM_H8_300 46 /* Hitachi H8/300 */

#define EM_H8_300H 47 /* Hitachi H8/300H */

#define EM_H8S 48 /* Hitachi H8S */

#define EM_H8_500 49 /* Hitachi H8/500 */

#define EM_IA_64 50 /* Intel Merced */

#define EM_MIPS_X 51 /* Stanford MIPS-X */

#define EM_COLDFIRE 52 /* Motorola Coldfire */

#define EM_68HC12 53 /* Motorola M68HC12 */

#define EM_MMA 54 /* Fujitsu MMA Multimedia Accelerator */

#define EM_PCP 55 /* Siemens PCP */

#define EM_NCPU 56 /* Sony nCPU embeeded RISC */

#define EM_NDR1 57 /* Denso NDR1 microprocessor */

#define EM_STARCORE 58 /* Motorola Start*Core processor */

#define EM_ME16 59 /* Toyota ME16 processor */

#define EM_ST100 60 /* STMicroelectronic ST100 processor */

#define EM_TINYJ 61 /* Advanced Logic Corp. Tinyj emb.fam */

#define EM_X86_64 62 /* AMD x86-64 architecture */

#define EM_PDSP 63 /* Sony DSP Processor */

#define EM_PDP10 64 /* Digital PDP-10 */

#define EM_PDP11 65 /* Digital PDP-11 */

#define EM_FX66 66 /* Siemens FX66 microcontroller */

#define EM_ST9PLUS 67 /* STMicroelectronics ST9+ 8/16 mc */

#define EM_ST7 68 /* STmicroelectronics ST7 8 bit mc */

#define EM_68HC16 69 /* Motorola MC68HC16 microcontroller */

#define EM_68HC11 70 /* Motorola MC68HC11 microcontroller */

#define EM_68HC08 71 /* Motorola MC68HC08 microcontroller */

#define EM_68HC05 72 /* Motorola MC68HC05 microcontroller */

#define EM_SVX 73 /* Silicon Graphics SVx */

#define EM_ST19 74 /* STMicroelectronics ST19 8 bit mc */

#define EM_VAX 75 /* Digital VAX */

#define EM_CRIS 76 /* Axis Communications 32-bit emb.proc */

#define EM_JAVELIN 77 /* Infineon Technologies 32-bit emb.proc */

#define EM_FIREPATH 78 /* Element 14 64-bit DSP Processor */

#define EM_ZSP 79 /* LSI Logic 16-bit DSP Processor */

#define EM_MMIX 80 /* Donald Knuth's educational 64-bit proc */

#define EM_HUANY 81 /* Harvard University machine-independent object files */

#define EM_PRISM 82 /* SiTera Prism */

#define EM_AVR 83 /* Atmel AVR 8-bit microcontroller */

#define EM_FR30 84 /* Fujitsu FR30 */

#define EM_D10V 85 /* Mitsubishi D10V */

#define EM_D30V 86 /* Mitsubishi D30V */

#define EM_V850 87 /* NEC v850 */

#define EM_M32R 88 /* Mitsubishi M32R */

#define EM_MN10300 89 /* Matsushita MN10300 */

#define EM_MN10200 90 /* Matsushita MN10200 */

#define EM_PJ 91 /* picoJava */

#define EM_OPENRISC 92 /* OpenRISC 32-bit embedded processor */

#define EM_ARC_COMPACT 93 /* ARC International ARCompact */

#define EM_XTENSA 94 /* Tensilica Xtensa Architecture */

#define EM_VIDEOCORE 95 /* Alphamosaic VideoCore */

#define EM_TMM_GPP 96 /* Thompson Multimedia General Purpose Proc */

#define EM_NS32K 97 /* National Semi. 32000 */

#define EM_TPC 98 /* Tenor Network TPC */

#define EM_SNP1K 99 /* Trebia SNP 1000 */

#define EM_ST200 100 /* STMicroelectronics ST200 */

#define EM_IP2K 101 /* Ubicom IP2xxx */

#define EM_MAX 102 /* MAX processor */

#define EM_CR 103 /* National Semi. CompactRISC */

#define EM_F2MC16 104 /* Fujitsu F2MC16 */

#define EM_MSP430 105 /* Texas Instruments msp430 */

#define EM_BLACKFIN 106 /* Analog Devices Blackfin DSP */

#define EM_SE_C33 107 /* Seiko Epson S1C33 family */

#define EM_SEP 108 /* Sharp embedded microprocessor */

#define EM_ARCA 109 /* Arca RISC */

#define EM_UNICORE 110 /* PKU-Unity & MPRC Peking Uni. mc series */

#define EM_EXCESS 111 /* eXcess configurable cpu */

#define EM_DXP 112 /* Icera Semi. Deep Execution Processor */

#define EM_ALTERA_NIOS2 113 /* Altera Nios II */

#define EM_CRX 114 /* National Semi. CompactRISC CRX */

#define EM_XGATE 115 /* Motorola XGATE */

#define EM_C166 116 /* Infineon C16x/XC16x */

#define EM_M16C 117 /* Renesas M16C */

#define EM_DSPIC30F 118 /* Microchip Technology dsPIC30F */

#define EM_CE 119 /* Freescale Communication Engine RISC */

#define EM_M32C 120 /* Renesas M32C */

/* reserved 121-130 */

#define EM_TSK3000 131 /* Altium TSK3000 */

#define EM_RS08 132 /* Freescale RS08 */

#define EM_SHARC 133 /* Analog Devices SHARC family */

#define EM_ECOG2 134 /* Cyan Technology eCOG2 */

#define EM_SCORE7 135 /* Sunplus S+core7 RISC */

#define EM_DSP24 136 /* New Japan Radio (NJR) 24-bit DSP */

#define EM_VIDEOCORE3 137 /* Broadcom VideoCore III */

#define EM_LATTICEMICO32 138 /* RISC for Lattice FPGA */

#define EM_SE_C17 139 /* Seiko Epson C17 */

#define EM_TI_C6000 140 /* Texas Instruments TMS320C6000 DSP */

#define EM_TI_C2000 141 /* Texas Instruments TMS320C2000 DSP */

#define EM_TI_C5500 142 /* Texas Instruments TMS320C55x DSP */

#define EM_TI_ARP32 143 /* Texas Instruments App. Specific RISC */

#define EM_TI_PRU 144 /* Texas Instruments Prog. Realtime Unit */

/* reserved 145-159 */

#define EM_MMDSP_PLUS 160 /* STMicroelectronics 64bit VLIW DSP */

#define EM_CYPRESS_M8C 161 /* Cypress M8C */

#define EM_R32C 162 /* Renesas R32C */

#define EM_TRIMEDIA 163 /* NXP Semi. TriMedia */

#define EM_QDSP6 164 /* QUALCOMM DSP6 */

#define EM_8051 165 /* Intel 8051 and variants */

#define EM_STXP7X 166 /* STMicroelectronics STxP7x */

#define EM_NDS32 167 /* Andes Tech. compact code emb. RISC */

#define EM_ECOG1X 168 /* Cyan Technology eCOG1X */

#define EM_MAXQ30 169 /* Dallas Semi. MAXQ30 mc */

#define EM_XIMO16 170 /* New Japan Radio (NJR) 16-bit DSP */

#define EM_MANIK 171 /* M2000 Reconfigurable RISC */

#define EM_CRAYNV2 172 /* Cray NV2 vector architecture */

#define EM_RX 173 /* Renesas RX */

#define EM_METAG 174 /* Imagination Tech. META */

#define EM_MCST_ELBRUS 175 /* MCST Elbrus */

#define EM_ECOG16 176 /* Cyan Technology eCOG16 */

#define EM_CR16 177 /* National Semi. CompactRISC CR16 */

#define EM_ETPU 178 /* Freescale Extended Time Processing Unit */

#define EM_SLE9X 179 /* Infineon Tech. SLE9X */

#define EM_L10M 180 /* Intel L10M */

#define EM_K10M 181 /* Intel K10M */

/* reserved 182 */

#define EM_AARCH64 183 /* ARM AARCH64 */

/* reserved 184 */

#define EM_AVR32 185 /* Amtel 32-bit microprocessor */

#define EM_STM8 186 /* STMicroelectronics STM8 */

#define EM_TILE64 187 /* Tilera TILE64 */

#define EM_TILEPRO 188 /* Tilera TILEPro */

#define EM_MICROBLAZE 189 /* Xilinx MicroBlaze */

#define EM_CUDA 190 /* NVIDIA CUDA */

#define EM_TILEGX 191 /* Tilera TILE-Gx */

#define EM_CLOUDSHIELD 192 /* CloudShield */

#define EM_COREA_1ST 193 /* KIPO-KAIST Core-A 1st gen. */

#define EM_COREA_2ND 194 /* KIPO-KAIST Core-A 2nd gen. */

#define EM_ARCV2 195 /* Synopsys ARCv2 ISA. */

#define EM_OPEN8 196 /* Open8 RISC */

#define EM_RL78 197 /* Renesas RL78 */

#define EM_VIDEOCORE5 198 /* Broadcom VideoCore V */

#define EM_78KOR 199 /* Renesas 78KOR */

#define EM_56800EX 200 /* Freescale 56800EX DSC */

#define EM_BA1 201 /* Beyond BA1 */

#define EM_BA2 202 /* Beyond BA2 */

#define EM_XCORE 203 /* XMOS xCORE */

#define EM_MCHP_PIC 204 /* Microchip 8-bit PIC(r) */

#define EM_INTELGT 205 /* Intel Graphics Technology */

/* reserved 206-209 */

#define EM_KM32 210 /* KM211 KM32 */

#define EM_KMX32 211 /* KM211 KMX32 */

#define EM_EMX16 212 /* KM211 KMX16 */

#define EM_EMX8 213 /* KM211 KMX8 */

#define EM_KVARC 214 /* KM211 KVARC */

#define EM_CDP 215 /* Paneve CDP */

#define EM_COGE 216 /* Cognitive Smart Memory Processor */

#define EM_COOL 217 /* Bluechip CoolEngine */

#define EM_NORC 218 /* Nanoradio Optimized RISC */

#define EM_CSR_KALIMBA 219 /* CSR Kalimba */

#define EM_Z80 220 /* Zilog Z80 */

#define EM_VISIUM 221 /* Controls and Data Services VISIUMcore */

#define EM_FT32 222 /* FTDI Chip FT32 */

#define EM_MOXIE 223 /* Moxie processor */

#define EM_AMDGPU 224 /* AMD GPU */

/* reserved 225-242 */

#define EM_RISCV 243 /* RISC-V */

#define EM_BPF 247 /* Linux BPF -- in-kernel virtual machine */

#define EM_CSKY 252 /* C-SKY */

#define EM_NUM 253

The e_version field serves the same role as the EI_VERSION byte in the e_ident array; and it indicates the version of the ELF specification that was used when creating the binary. Currently, the only possible value is 1 (EV_CURRENT) to indicate version 1 of the specification.

/* Legal values for e_version (version). */

#define EV_NONE 0 /* Invalid ELF version */

#define EV_CURRENT 1 /* Current version */

#define EV_NUM 2

e_entry

The e_entry field denotes the entry point of the binary; this is the virtual address at which execution should start.

e_phoff and e_shoff

e_phoff and e_shoff indicate the file offsets to the beginning of the program header table and the section header table. The offsets can also be set to zero to indicate that the file does not contain a program header or section header table. These fields are file offsets, meaning the number of bytes read into the file to get to the headers. In contrast to the e_entry field, e_phoff and e_shoff are not virtual addresses.

e_flags

ARM binaries can set ARM-specific flags in the e_flags field to indicate additional details about the interface they expect from the embedded operating system such as file format conventions, stack organization, etc. For x86 binaries, e_flags is typically set to zero and not of interest.

e_ehsize

The e_ehsize field specifies the size of the executable header, in bytes. For 64-bit x86 binaries, the executable header size is always 64 bytes.

e_*entsize and e_*num

The e_phoff and e_shoff fields point to the file offsets where the program header and section header tables begin. The e_phentsize and e_phnum fields provide program header table entry size and program header table entry count. The e_shentsize and e_shnum fields give the size of the section header table entry and count.

e_shstrndx

The e_shstrndx field contains the index in the section header table of the header associated with a special string table section called .shstrtab. This is a dedicated section that contains a table of null-terminated ASCII strings, which store the names of all the sections in the binary. It is used by ELF processing tools such as readelf to correctly show the names of sections.

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ readelf -x .shstrtab a.out

Hex dump of section '.shstrtab':

0x00000000 002e7379 6d746162 002e7374 72746162 ..symtab..strtab

0x00000010 002e7368 73747274 6162002e 696e7465 ..shstrtab..inte

0x00000020 7270002e 6e6f7465 2e676e75 2e70726f rp..note.gnu.pro

0x00000030 70657274 79002e6e 6f74652e 676e752e perty..note.gnu.

0x00000040 6275696c 642d6964 002e6e6f 74652e41 build-id..note.A

0x00000050 42492d74 6167002e 676e752e 68617368 BI-tag..gnu.hash

0x00000060 002e6479 6e73796d 002e6479 6e737472 ..dynsym..dynstr

0x00000070 002e676e 752e7665 7273696f 6e002e67 ..gnu.version..g

0x00000080 6e752e76 65727369 6f6e5f72 002e7265 nu.version_r..re

0x00000090 6c612e64 796e002e 72656c61 2e706c74 la.dyn..rela.plt

0x000000a0 002e696e 6974002e 706c742e 676f7400 ..init..plt.got.

0x000000b0 2e706c74 2e736563 002e7465 7874002e .plt.sec..text..

0x000000c0 66696e69 002e726f 64617461 002e6568 fini..rodata..eh

0x000000d0 5f667261 6d655f68 6472002e 65685f66 _frame_hdr..eh_f

0x000000e0 72616d65 002e696e 69745f61 72726179 rame..init_array

0x000000f0 002e6669 6e695f61 72726179 002e6479 ..fini_array..dy

0x00000100 6e616d69 63002e64 61746100 2e627373 namic..data..bss

0x00000110 002e636f 6d6d656e 7400 ..comment.

Section headers

The code and data in an ELF binary are logically divided into contiguous nonoverlapping chunks called sections. Sections don’t have any predetermined structure. Every section is described by a section header, which denotes the properties of the section and allows you to locate the bytes belonging to the section. The section headers for all sections in a binary are in the section header table.

/* Section header. */

typedef struct

{

Elf32_Word sh_name; /* Section name (string tbl index) */

Elf32_Word sh_type; /* Section type */

Elf32_Word sh_flags; /* Section flags */

Elf32_Addr sh_addr; /* Section virtual addr at execution */

Elf32_Off sh_offset; /* Section file offset */

Elf32_Word sh_size; /* Section size in bytes */

Elf32_Word sh_link; /* Link to another section */

Elf32_Word sh_info; /* Additional section information */

Elf32_Word sh_addralign; /* Section alignment */

Elf32_Word sh_entsize; /* Entry size if section holds table */

} Elf32_Shdr;

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Word sh_name; /* Section name (string tbl index) */

Elf64_Word sh_type; /* Section type */

Elf64_Xword sh_flags; /* Section flags */

Elf64_Addr sh_addr; /* Section virtual addr at execution */

Elf64_Off sh_offset; /* Section file offset */

Elf64_Xword sh_size; /* Section size in bytes */

Elf64_Word sh_link; /* Link to another section */

Elf64_Word sh_info; /* Additional section information */

Elf64_Xword sh_addralign; /* Section alignment */

Elf64_Xword sh_entsize; /* Entry size if section holds table */

} Elf64_Shdr;

sh_name

The first field in a section header is called sh_name. If set, it contains an index into the string table. If the index is zero, it means the section does not have a name. When analysing malware, do not rely on the contents of the sh_name field, because the malware may use intentionally misleading section names.

The .shstrtab section contains an array of NULL-terminated strings, one for every section name. The index of the section header describing the string table is given in the e_shstrndx field of the executable header. This allows tools like readelf to easily find the .shstrtab section and then index it with the sh_name field of every section header (including the header of .shstrtab) to find the string describing the name of the section in question.

sh_type

Every section has a type, indicated by an integer field called sh_type, that tells the linker something about the structure of a section’s contents.

/* Legal values for sh_type (section type). */

#define SHT_NULL 0 /* Section header table entry unused */

#define SHT_PROGBITS 1 /* Program data */

#define SHT_SYMTAB 2 /* Symbol table */

#define SHT_STRTAB 3 /* String table */

#define SHT_RELA 4 /* Relocation entries with addends */

#define SHT_HASH 5 /* Symbol hash table */

#define SHT_DYNAMIC 6 /* Dynamic linking information */

#define SHT_NOTE 7 /* Notes */

#define SHT_NOBITS 8 /* Program space with no data (bss) */

#define SHT_REL 9 /* Relocation entries, no addends */

#define SHT_SHLIB 10 /* Reserved */

#define SHT_DYNSYM 11 /* Dynamic linker symbol table */

#define SHT_INIT_ARRAY 14 /* Array of constructors */

#define SHT_FINI_ARRAY 15 /* Array of destructors */

#define SHT_PREINIT_ARRAY 16 /* Array of pre-constructors */

#define SHT_GROUP 17 /* Section group */

#define SHT_SYMTAB_SHNDX 18 /* Extended section indices */

#define SHT_NUM 19 /* Number of defined types. */

#define SHT_LOOS 0x60000000 /* Start OS-specific. */

#define SHT_GNU_ATTRIBUTES 0x6ffffff5 /* Object attributes. */

#define SHT_GNU_HASH 0x6ffffff6 /* GNU-style hash table. */

#define SHT_GNU_LIBLIST 0x6ffffff7 /* Prelink library list */

#define SHT_CHECKSUM 0x6ffffff8 /* Checksum for DSO content. */

#define SHT_LOSUNW 0x6ffffffa /* Sun-specific low bound. */

#define SHT_SUNW_move 0x6ffffffa

#define SHT_SUNW_COMDAT 0x6ffffffb

#define SHT_SUNW_syminfo 0x6ffffffc

#define SHT_GNU_verdef 0x6ffffffd /* Version definition section. */

#define SHT_GNU_verneed 0x6ffffffe /* Version needs section. */

#define SHT_GNU_versym 0x6fffffff /* Version symbol table. */

#define SHT_HISUNW 0x6fffffff /* Sun-specific high bound. */

#define SHT_HIOS 0x6fffffff /* End OS-specific type */

#define SHT_LOPROC 0x70000000 /* Start of processor-specific */

#define SHT_HIPROC 0x7fffffff /* End of processor-specific */

#define SHT_LOUSER 0x80000000 /* Start of application-specific */

#define SHT_HIUSER 0x8fffffff /* End of application-specific */

Sections with type SHT_PROGBITS contain program data, such as machine instructions or constants. These sections have no particular structure for the linker to parse.

SHT_SYMTAB is the type for static symbol tables, SHT_DYNSYM for symbol tables used by the dynamic linker, and SHT_STRTAB for string tables.

Sections with type SHT_REL or SHT_RELA are particularly important for the linker because they contain relocation entries in a well-defined format. Each relocation entry tells the linker about a particular location in the binary where a relocation is needed and which symbol the relocation should be resolved to.

Sections of type SHT_DYNAMIC contain information needed for dynamic linking.

sh_flags

Section flags describe additional information about a section.

/* Legal values for sh_flags (section flags). */

#define SHF_WRITE (1 << 0) /* Writable */

#define SHF_ALLOC (1 << 1) /* Occupies memory during execution */

#define SHF_EXECINSTR (1 << 2) /* Executable */

#define SHF_MERGE (1 << 4) /* Might be merged */

#define SHF_STRINGS (1 << 5) /* Contains nul-terminated strings */

#define SHF_INFO_LINK (1 << 6) /* `sh_info' contains SHT index */

#define SHF_LINK_ORDER (1 << 7) /* Preserve order after combining */

#define SHF_OS_NONCONFORMING (1 << 8) /* Non-standard OS specific handling

required */

#define SHF_GROUP (1 << 9) /* Section is member of a group. */

#define SHF_TLS (1 << 10) /* Section hold thread-local data. */

#define SHF_COMPRESSED (1 << 11) /* Section with compressed data. */

#define SHF_MASKOS 0x0ff00000 /* OS-specific. */

#define SHF_MASKPROC 0xf0000000 /* Processor-specific */

#define SHF_GNU_RETAIN (1 << 21) /* Not to be GCed by linker. */

#define SHF_ORDERED (1 << 30) /* Special ordering requirement

(Solaris). */

#define SHF_EXCLUDE (1U << 31) /* Section is excluded unless

referenced or allocated (Solaris).*/

SHF_WRITE indicates the section is writable at runtime. This makes it easy to distinguish between sections that contain static data and those that contain variables.

The SHF_ALLOC flag indicates that the contents of the section are to be loaded into virtual memory when executing the binary (the actual loading happens using the segment view of the binary, not the section view).

SHF_EXECINSTR indicates the section contains executable instructions, which is useful to know when disassembling a binary.

sh_addr, sh_offset, and sh_size

The sh_addr, sh_offset, and sh_size fields describe the virtual address, file offset (in bytes from the start of the file), and size (in bytes) of the section, respectively.

The linker sometimes needs to know at which addresses particular pieces of code and data will end up at runtime to do relocations. The sh_addr field provides this information. Sections that aren’t intended to be loaded into virtual memory when setting up the process have an sh_addr value of zero.

sh_link

Sometimes there are relationships between sections that the linker needs to know about. The sh_link field makes these relationships explicit by denoting the index (in the section header table) of the related section.

sh_info

The sh_info field contains additional information about the section. The meaning of the additional information varies depending on the section type. For example, for relocation sections, sh_info denotes the index of the section to which the relocations are to be applied.

sh_addralign

Some sections may need to be aligned in memory in a particular way for efficiency of memory accesses. These alignment

requirements are specified in the sh_addralign field.

sh_entsize

Some sections, such as symbol tables or relocation tables, contain a table of well-defined data structures. For such sections, the sh_entsize field indicates the size in bytes of each entry in the table. When the field is unused, it is set to zero.

Sections

Typical ELF files on a GNU/Linux system are organized into a series of standard sections. the output of readelf conforms closely to the structure of a section header.

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ readelf --sections --wide a.out

There are 31 section headers, starting at offset 0x3698:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 0000000000000318 000318 00001c 00 A 0 0 1

[ 2] .note.gnu.property NOTE 0000000000000338 000338 000030 00 A 0 0 8

[ 3] .note.gnu.build-id NOTE 0000000000000368 000368 000024 00 A 0 0 4

[ 4] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 000000000000038c 00038c 000020 00 A 0 0 4

[ 5] .gnu.hash GNU_HASH 00000000000003b0 0003b0 000024 00 A 6 0 8

[ 6] .dynsym DYNSYM 00000000000003d8 0003d8 0000a8 18 A 7 1 8

[ 7] .dynstr STRTAB 0000000000000480 000480 00008d 00 A 0 0 1

[ 8] .gnu.version VERSYM 000000000000050e 00050e 00000e 02 A 6 0 2

[ 9] .gnu.version_r VERNEED 0000000000000520 000520 000030 00 A 7 1 8

[10] .rela.dyn RELA 0000000000000550 000550 0000c0 18 A 6 0 8

[11] .rela.plt RELA 0000000000000610 000610 000018 18 AI 6 24 8

[12] .init PROGBITS 0000000000001000 001000 00001b 00 AX 0 0 4

[13] .plt PROGBITS 0000000000001020 001020 000020 10 AX 0 0 16

[14] .plt.got PROGBITS 0000000000001040 001040 000010 10 AX 0 0 16

[15] .plt.sec PROGBITS 0000000000001050 001050 000010 10 AX 0 0 16

[16] .text PROGBITS 0000000000001060 001060 000112 00 AX 0 0 16

[17] .fini PROGBITS 0000000000001174 001174 00000d 00 AX 0 0 4

[18] .rodata PROGBITS 0000000000002000 002000 000012 00 A 0 0 4

[19] .eh_frame_hdr PROGBITS 0000000000002014 002014 000034 00 A 0 0 4

[20] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000002048 002048 0000ac 00 A 0 0 8

[21] .init_array INIT_ARRAY 0000000000003db8 002db8 000008 08 WA 0 0 8

[22] .fini_array FINI_ARRAY 0000000000003dc0 002dc0 000008 08 WA 0 0 8

[23] .dynamic DYNAMIC 0000000000003dc8 002dc8 0001f0 10 WA 7 0 8

[24] .got PROGBITS 0000000000003fb8 002fb8 000048 08 WA 0 0 8

[25] .data PROGBITS 0000000000004000 003000 000010 00 WA 0 0 8

[26] .bss NOBITS 0000000000004010 003010 000008 00 WA 0 0 1

[27] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 003010 00002d 01 MS 0 0 1

[28] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 003040 000360 18 29 18 8

[29] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 0033a0 0001db 00 0 0 1

[30] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00357b 00011a 00 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

D (mbind), l (large), p (processor specific)

.init and .fini

The .init section contains executable code that performs initialisation tasks and needs to run before any other code in the binary is executed (SHF_EXECINSTR flag).

The system executes the code in the .init section before transferring control to the main entry point of the binary, like a constructor. The .fini section is analogous to the .init section, except that it runs after the main program completes, functioning as a kind of destructor.

.text

The .text section is where the main code of the program resides, and is often the main focus of binary analysis or reverse engineering. The [16] .text section has type SHT_PROGBITS because it contains user-defined code, and the section indicate that the section is executable but not writable.

Besides the application-specific code compiled from the program’s source, the .text section of a binary compiled by gcc usually contains a number of standard functions that perform initialisation and finalisation tasks, such as _start, register_tm_clones, and frame_dummy.

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ objdump -M intel -d a.out

a.out: file format elf64-x86-64

...

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000001060 <_start>:

1060: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1064: 31 ed xor ebp,ebp

1066: 49 89 d1 mov r9,rdx

1069: 5e pop rsi

106a: 48 89 e2 mov rdx,rsp

106d: 48 83 e4 f0 and rsp,0xfffffffffffffff0

1071: 50 push rax

1072: 54 push rsp

1073: 45 31 c0 xor r8d,r8d

1076: 31 c9 xor ecx,ecx

1078: 48 8d 3d ca 00 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0xca] # 1149 <main>

107f: ff 15 53 2f 00 00 call QWORD PTR [rip+0x2f53] # 3fd8 <__libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.34>

1085: f4 hlt

1086: 66 2e 0f 1f 84 00 00 cs nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

108d: 00 00 00

...

0000000000001149 <main>:

1149: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

114d: 55 push rbp

114e: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

1151: 48 83 ec 10 sub rsp,0x10

1155: 89 7d fc mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],edi

1158: 48 89 75 f0 mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x10],rsi

115c: 48 8d 05 a1 0e 00 00 lea rax,[rip+0xea1] # 2004 <_IO_stdin_used+0x4>

1163: 48 89 c7 mov rdi,rax

1166: e8 e5 fe ff ff call 1050 <puts@plt>

116b: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

1170: c9 leave

1171: c3 ret

The entry point of the binary, does not point to main, but to the beginning of _start. _start contains an instruction that moves the address of main into the rdi register, which is one of the registers used to pass parameters for function calls on the x64 platform. Then, _start calls a function called __libc_start_main. It resides in the .plt section, which means the function is part of a shared library. And __libc_start_main finally calls to the address of main to begin execution of the user-defined code.

.bss, .data, and .rodata

Because code sections are usually not writable, variables are kept in one or more dedicated sections, which are writable. Constant data is usually also kept in its own section to keep the binary neatly organised, though compilers do sometimes output constant data in code sections. Modern versions of gcc and clang do not mix code and data, but Visual Studio sometimes does, making disassembly difficult because it is not always clear which bytes represent instructions and which represent data.

The .rodata section is dedicated to storing constant values, and not writable. The default values of initialised variables are stored in the .data section, which is marked as writable since the values of variables may change

at runtime. The .bss section reserves space for uninitialised variables.

Unlike .rodata and .data, which have type SHT_PROGBITS, the .bss section has type SHT_NOBITS (.bss does not occupy any bytes in the binary as it exists on disk). This is because it is only a directive to allocate a properly sized block of memory for uninitialised variables when setting up an execution environment for the binary. Variables that live in .bss are zero initialised, and the section is marked as writable.

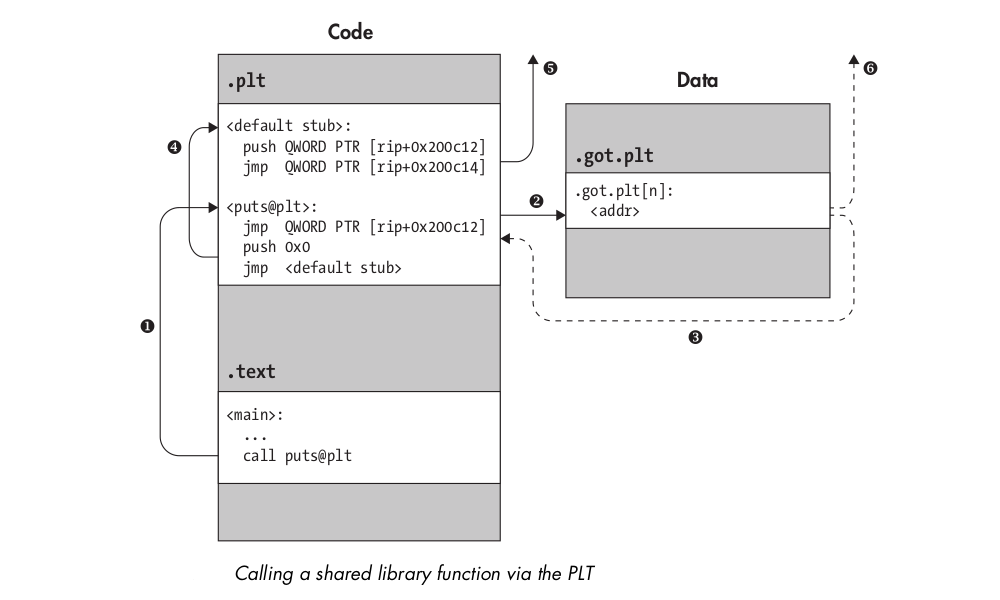

.plt, .got, and .got.plt

Lazy binding ensures that the dynamic linker never needlessly wastes time on relocations; it only performs those relocations that are truly needed at runtime. On Linux, lazy binding is the default behaviour of the dynamic linker.

Lazy binding in Linux ELF binaries is implemented with the help of two special sections, called the Procedure Linkage Table (.plt) and the Global Offset Table (.got). ELF binaries often contain a separate GOT section called .got.plt for use in conjunction with .plt in the lazy binding process. More specifically, .got is for relocations regarding global ‘variables’ while .got.plt is an auxiliary section to act together with .plt when resolving procedures absolute addresses.

.plt is a code section that contains executable code, just like .text, while .got.plt is a data section. The PLT consists entirely of stubs of a well-defined format, dedicated to directing calls from the .text section to the appropriate library location.

Example from “Practical Binary Analysis”:

To call the puts function (part of the libc library):

Make a call to the corresponding PLT stub,

puts@plt.The PLT stub begins with an indirect jump instruction, which jumps to an address stored in the

.got.pltsection.Before the lazy binding has happened, this address is simply the address of the next instruction in the function stub, which is a

pushinstruction. Thus, the indirect jump simply transfers control to the instruction directly after it.The

pushinstruction pushes an integer (in this case,0x0) onto the stack. This integer serves as an identifier for the PLT stub in question. Subsequently, the next instruction jumps to the common default stub shared among all PLT function stubs.The default stub pushes another identifier (taken from the GOT), identifying the executable itself, and then jumps (indirectly, again through the GOT) to the dynamic linker.

.plt.got is an alternative PLT that uses read-only .got entries instead of .got.plt entries. It is used when

enabling the ld option -z now at compile time, telling ld that you want to use “now binding.” This has the same effect as LD_BIND_NOW=1, but by informing ld at compile time, you allow it to place GOT entries in .got for enhanced security and use 8-byte .plt.got entries instead of larger 16-byte .plt entries.

.rel.* and .rela.*

rela.* sections are of type SHT_RELA, meaning that they contain information used by the linker. Each section of type SHT_RELA is a table of relocation entries, with each entry detailing a particular address where a relocation needs to be applied, as well as instructions on how to resolve the particular value that needs to be plugged in at this address. What all relocation types have in common is that they specify an offset at which to apply the relocation. For normal binary analysis tasks it is not necessary to know the details of how to compute the value to plug in at the offset for a particular relocation type.

.dynamic

The .dynamic section functions as a “road map” for the operating system and dynamic linker when loading and setting up an ELF binary for execution. The .dynamic section contains a table of Elf64_Dyn structures, also referred to as tags. There are different types of tags, each of which comes with an associated value.

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ readelf --dynamic a.out

Dynamic section at offset 0x2dc8 contains 27 entries:

Tag Type Name/Value

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libc.so.6]

0x000000000000000c (INIT) 0x1000

0x000000000000000d (FINI) 0x1174

0x0000000000000019 (INIT_ARRAY) 0x3db8

0x000000000000001b (INIT_ARRAYSZ) 8 (bytes)

0x000000000000001a (FINI_ARRAY) 0x3dc0

0x000000000000001c (FINI_ARRAYSZ) 8 (bytes)

0x000000006ffffef5 (GNU_HASH) 0x3b0

0x0000000000000005 (STRTAB) 0x480

0x0000000000000006 (SYMTAB) 0x3d8

0x000000000000000a (STRSZ) 141 (bytes)

0x000000000000000b (SYMENT) 24 (bytes)

0x0000000000000015 (DEBUG) 0x0

0x0000000000000003 (PLTGOT) 0x3fb8

0x0000000000000002 (PLTRELSZ) 24 (bytes)

0x0000000000000014 (PLTREL) RELA

0x0000000000000017 (JMPREL) 0x610

0x0000000000000007 (RELA) 0x550

0x0000000000000008 (RELASZ) 192 (bytes)

0x0000000000000009 (RELAENT) 24 (bytes)

0x000000000000001e (FLAGS) BIND_NOW

0x000000006ffffffb (FLAGS_1) Flags: NOW PIE

0x000000006ffffffe (VERNEED) 0x520

0x000000006fffffff (VERNEEDNUM) 1

0x000000006ffffff0 (VERSYM) 0x50e

0x000000006ffffff9 (RELACOUNT) 3

0x0000000000000000 (NULL) 0x0

Tags of type DT_NEEDED inform the dynamic linker about dependencies of the executable. The DT_VERNEED and DT_VERNEEDNUM tags specify the starting address and number of entries of the version dependency table, which indicates the expected version of the various dependencies of the executable.

In addition to listing dependencies, the .dynamic section also contains pointers to other important information required by the dynamic linker, like the dynamic string table, dynamic symbol table, .got.pltsection, and dynamic relocation section pointed to by tags of type DT_STRTAB, DT_SYMTAB, DT_PLTGOT, and DT_RELA.

.init_array and .fini_array

The .init_array section contains an array of pointers to functions to use as constructors. Each of these functions is called in turn when the binary is initialised, before main is called. While the .init section contains a single startup function that performs some crucial initialisation needed to start the executable, .init_array is a data section that can contain as many function pointers as wanted, including pointers to user made custom constructors. In gcc, these can be marked as constructor functions in the C source files by decorating them with __attribute__((constructor)).

To show the contents of .init_array:

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ objdump -d --section .init_array a.out

a.out: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .init_array:

0000000000003db8 <__frame_dummy_init_array_entry>:

3db8: 40 11 00 00 00 00 00 00 @.......

40 11 00 00 00 00 00 00 is little-endian-speak for the address 0x1140. Using objdump to shows that this is indeed the starting address of the frame_dummy function:

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ objdump -d a.out | grep '<frame_dummy>'

0000000000001140 <frame_dummy>:

.fini_array is analogous to .init_array, except that .fini_array contains pointers to destructors rather than constructors.

The pointers contained in .init_array and .fini_array are easy to change, making them convenient places to insert hooks that add initialisation or finalisation code to the binary to modify its behaviour.

Binaries produced by older gcc versions may contain sections called .ctors and .dtors instead of .init_array and .fini_array.

shstrtab, .symtab, .strtab, .dynsym, and .dynstr

The .shstrtab section is an array of NULL-terminated strings that contain the names of all the sections in the binary. It is indexed by the section headers to allow tools like readelf to find out the names of the sections.

The .symtab section contains a symbol table, a table of Elf64_Sym structures, each of which associates a symbolic name with a piece of code or data elsewhere in the binary, such as a function or variable. The actual strings containing the symbolic names are located in the .strtab section. These strings are pointed to by the Elf64_Sym structures. In practice, binaries will often be stripped, meaning the .symtab and .strtab tables are removed.

The .dynsym and .dynstr sections are analogous to .symtab and .strtab, except that they contain symbols and strings needed for dynamic linking rather than static linking. These cannot be stripped.

Program headers

The section view of an ELF binary is meant for static linking purposes only. The segment view is used by the OS and dynamic linker when loading an ELF into a process for execution to locate the relevant code and data and decide what to load into virtual memory. The program header table provides a segment view of the binary.

/* Program segment header. */

typedef struct

{

Elf32_Word p_type; /* Segment type */

Elf32_Off p_offset; /* Segment file offset */

Elf32_Addr p_vaddr; /* Segment virtual address */

Elf32_Addr p_paddr; /* Segment physical address */

Elf32_Word p_filesz; /* Segment size in file */

Elf32_Word p_memsz; /* Segment size in memory */

Elf32_Word p_flags; /* Segment flags */

Elf32_Word p_align; /* Segment alignment */

} Elf32_Phdr;

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Word p_type; /* Segment type */

Elf64_Word p_flags; /* Segment flags */

Elf64_Off p_offset; /* Segment file offset */

Elf64_Addr p_vaddr; /* Segment virtual address */

Elf64_Addr p_paddr; /* Segment physical address */

Elf64_Xword p_filesz; /* Segment size in file */

Elf64_Xword p_memsz; /* Segment size in memory */

Elf64_Xword p_align; /* Segment alignment */

} Elf64_Phdr;

The program header of hello.c as shown by readelf:

nina@tardis:~/Development/elf$ readelf --wide --segments a.out

Elf file type is DYN (Position-Independent Executable file)

Entry point 0x1060

There are 13 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000040 0x0000000000000040 0x0000000000000040 0x0002d8 0x0002d8 R 0x8

INTERP 0x000318 0x0000000000000318 0x0000000000000318 0x00001c 0x00001c R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x000628 0x000628 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x001000 0x0000000000001000 0x0000000000001000 0x000181 0x000181 R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x002000 0x0000000000002000 0x0000000000002000 0x0000f4 0x0000f4 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x002db8 0x0000000000003db8 0x0000000000003db8 0x000258 0x000260 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x002dc8 0x0000000000003dc8 0x0000000000003dc8 0x0001f0 0x0001f0 RW 0x8

NOTE 0x000338 0x0000000000000338 0x0000000000000338 0x000030 0x000030 R 0x8

NOTE 0x000368 0x0000000000000368 0x0000000000000368 0x000044 0x000044 R 0x4

GNU_PROPERTY 0x000338 0x0000000000000338 0x0000000000000338 0x000030 0x000030 R 0x8

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x002014 0x0000000000002014 0x0000000000002014 0x000034 0x000034 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x000000 0x000000 RW 0x10

GNU_RELRO 0x002db8 0x0000000000003db8 0x0000000000003db8 0x000248 0x000248 R 0x1

Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections...

00

01 .interp

02 .interp .note.gnu.property .note.gnu.build-id .note.ABI-tag .gnu.hash .dynsym .dynstr .gnu.version .gnu.version_r .rela.dyn .rela.plt

03 .init .plt .plt.got .plt.sec .text .fini

04 .rodata .eh_frame_hdr .eh_frame

05 .init_array .fini_array .dynamic .got .data .bss

06 .dynamic

07 .note.gnu.property

08 .note.gnu.build-id .note.ABI-tag

09 .note.gnu.property

10 .eh_frame_hdr

11

12 .init_array .fini_array .dynamic .got

p_type

The p_type field identifies the type of the segment. Important values for this field include PT_LOAD, PT_DYNAMIC, and PT_INTERP.

There are usually at least two PT_LOAD segments, one for the nonwritable sections and one for the writable data sections. The PT_INTERP segment contains the .interp section, which provides the name of the interpreter that is to be used to load the binary. The PT_DYNAMIC segment contains the .dynamic section, which tells the interpreter how to parse and prepare the binary for execution. The PT_PHDR segment, holds the program header table.

p_flags

The PF_X flag indicates that the segment is executable and is set for code segments (readelf displays it as an E instead of an X). The PF_W flag means that the segment is writable, and is normally set only for writable data segments, never for code segments. PF_R means that the segment is readable, as is normally the case for both code and data segments.

p_offset, p_vaddr, p_paddr, p_filesz, and p_memsz

The p_offset, p_vaddr, and p_filesz fields are analogous to the sh_offset, sh_addr, and sh_size fields in a section header, and specify the file offset at which the segment starts, the virtual address at which it is to be loaded, and the file size of the segment, respectively. For loadable segments, p_vaddr must be equal to p_offset, modulo the page size (typically 4,096 bytes).

p_align

The p_align field is analogous to the sh_addralign field in a section header. It indicates the required memory alignment (in bytes) for the segment. If p_align is not set to 0 or 1, then its value must be a power of 2, and p_vaddr must be equal to p_offset, modulo p_align.